Every time another Black person is murdered by the police, it’s easy to point to a single officer as the culprit. George Floyd was killed under the knee of officer Derek Chauvin — we saw it ourselves. But Chauvin is just one officer in a culture of police violence, and policing is just one of the systems responsible for taking Black lives. COVID-19 exposed a number of the others.

It’s no coincidence that Black people, who are more likely to be killed by the police, are also dying at disproportionate rates of COVID-19. While some say it’s due to the prevalence of underlying health issues like diabetes and high blood pressure in the Black community, the conversation doesn’t end there, and pointing a finger at these conditions misses the bigger picture. We need to ask ourselves — how did we end up here?

The Black community is not inherently vulnerable to COVID-19. We’ve been made vulnerable through decades of unequal access to health care. We are made vulnerable every time a doctor or other health care provider dismisses us because they don’t believe our symptoms. We are made vulnerable through over-policing, which has led to not only our murders, but to our overrepresentation in jails and prisons, where the virus is spreading rapidly and has already killed hundreds. Even though public health experts have warned of the severe risk that incarcerated people face due to the conditions they live in, most have been left to languish as COVID-19 threatens to turn their detention into a death sentence.

In fact, jails and prisons are where multiple systemic failings that take Black lives converge — over-policing, over-incarceration, inadequate health care, and the deadly result.

When we say Black Lives Matter, we’re talking about more than police brutality. We’re talking about incarceration, health care, housing, education, and economics — all the different components of a broader system that has created the reality we see today, where Black people are incarcerated at more than five times the rate of white people, where Black people are given harsher sentences for the same offenses, where Black people are more likely to be held on bail pretrial, and where Black people are dying not only at the hands of police, but because of an unequal health care system. Black lives should matter in all stages of life — and to honor that truth, we must radically transform the system from its roots.

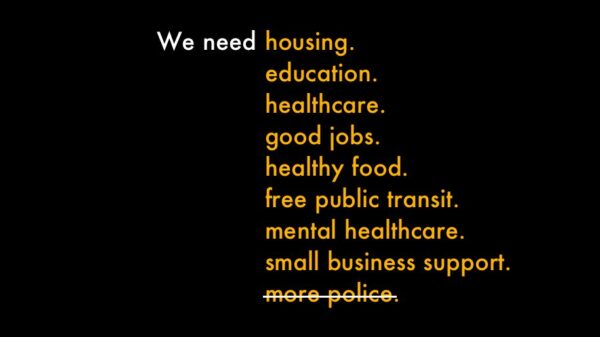

Systemic problems aren’t easy to fix, but we can take steps toward progress by re-examining the way we fund and rely on law enforcement in this country. A huge amount of public resources are put toward law enforcement agencies, at the expense of critical social services like education and health care. This doesn’t make us safer. It puts Black lives in danger of police brutality and of getting ensnared in the mass incarceration system. More law enforcement is not the answer. It’s what got us here in the first place.

Our culture of law enforcement puts the police in places they don’t need to be. Police don’t have to be the first responders to all crises, and they shouldn’t be. Social workers, doctors, and others can serve in place of police for issues including mental health crises, domestic violence, addiction, and homelessness. However, to create this reality we need to de-prioritize law enforcement — and cutting funding is a good start. Lawmakers should divert funding for police departments and put it to better use in community-led initiatives. Investing in services like health care and education will reduce the role of police in society, protect Black lives, and shift the focus to helping people rather than harming them.

When I co-founded Black Lives Matter almost seven years ago, the conversation about police brutality was just beginning to enter the mainstream discourse — not because police violence was anything new, but because of the work of activists and advocates who brought the issue to light with the help of technology that allows us to capture incidents on our phones. Today, more people are rallying for Black Lives than I would have ever imagined. That in itself is a sign of progress. But to turn Black Lives Matter into more than a rally cry, we must roll up our sleeves and do the work. Let’s tear down systems that harm us and strengthen systems that will advance true equality.

Let’s make sure that Black life matters at every stage and in every facet of society, well before a cop has his knee on a man’s neck.

Patrisse Cullors is a co-founder of Black Lives Matter.