Any time you are involved with the “Child Protective Services” (CPS) or the “child welfare” system, it could have big effects on your family that last a long time. But, as a parent, you do have rights. It is important to know what these rights are and use them to protect your family.

Below is information on how a CPS investigation works and your rights during the investigation.

WHAT ARE MY RIGHTS AS A PARENT DURING A CPS INVESTIGATION?

What is “Child Protective Services” or “CPS”?

In the state of California, “Child Protective Services” (CPS) is a county-run government agency often known as the child welfare and foster care system.

CPS agencies’ main job is to investigate reports of child abuse and neglect to decide whether a child should be removed from their home. They are also responsible for providing care of children removed from their homes under the supervision of the Juvenile Dependency Court. CPS does not provide supportive services to families without the risk of child removal. CPS also works closely with other agencies like law enforcement.

Depending on which county you live in, CPS can be called something different like “Department of Child and Family Services” (DCFS), “Children and Family Services” (CFS), “Child Welfare Services” (CWS), or other similar names.

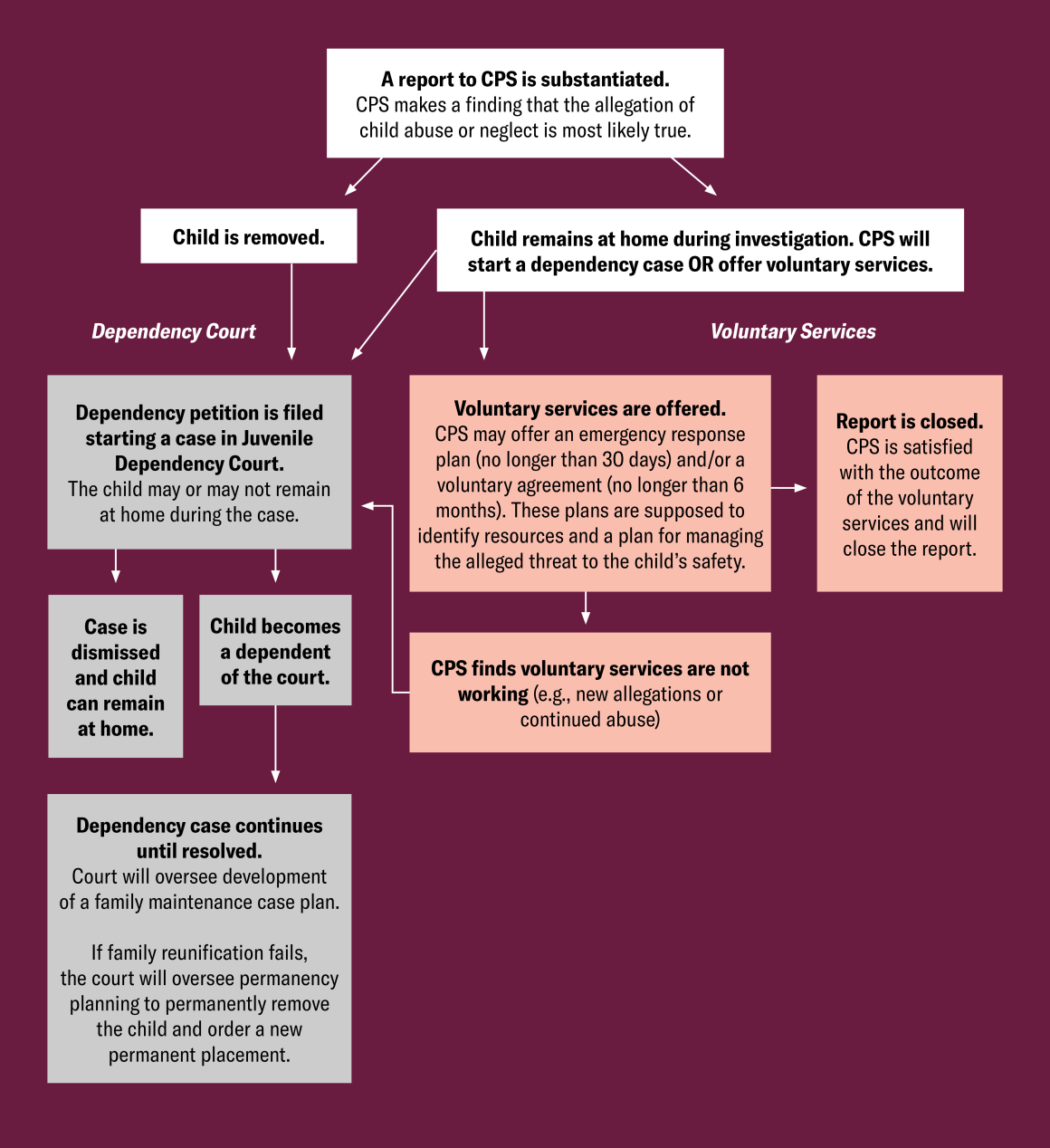

How do CPS investigations work?

CPS INVESTIGATIONS

Do I have the right to ask a CPS worker for more information if they come to visit my home?

Yes. If a CPS investigator comes to your home, you have the right to request identification. You also have the right to know the specific allegations made against you (i.e., more information than just “child abuse” or “child neglect”). Exercising your right to know the allegations does not mean you have to let the investigator into your home.

Do I have a right to know who made a CPS report against me and what was said?

No. The identity of the person who reports suspected child abuse or neglect, even if known by CPS, cannot be disclosed to the family or anyone else not directly involved in the CPS investigation. However, you have a right to know the specific allegations made against you. You can also contact CPS and ask for a copy of the report.

Do I have to let a CPS worker into my home if they come to visit?

Generally, no. You do not have to let a CPS worker enter your home unless they have a valid search warrant or declare an emergency.

A search warrant is only valid if it is dated and signed by a judge. Any search done under a search warrant must be limited only to what is specified in the warrant. You can ask to review the search warrant and look for where the date and judge signature is. You should also make sure the address where the warrant is being served is correct and matches the location being searched.

Examples of valid emergencies include a child requiring immediate medical attention or a child in danger of serious harm. If a CPS worker alleges there is an emergency, you can ask them to be specific. If you feel comfortable, you can also bring your children to the door to show the CPS worker that they are safe and there is no emergency.

Even if the CPS worker arrives with a police officer, they must have a warrant or declare there are emergency circumstances to enter your home. If there is no warrant and no emergency and you do not want to allow the investigator in your home, you can say something like, “Sorry, this isn’t a good time for me, but I’d be happy to schedule a visit on a later date.” By offering an alternative date like the next day or later in the week, you can plan to be more prepared for a visit, but also show cooperation. If you refuse any visit, that can be used as evidence against you later in the investigation. Depending on the situation, follow-up visits can take place either at home or the CPS office.

If a CPS worker or a police officer enters your home forcefully, you should not physically resist but should express clearly that you did not consent. If possible, try to write down the names of the CPS workers and/or police officers.

When can a child be removed from their home?

CPS can remove a child from their home, including during the first in-person visit, if there is:

- Consent. If the parents sign a written agreement to have CPS remove the child.

- Serious Danger. If CPS or law enforcement reasonably believe a child is in immediate danger, even if they don’t have a warrant, they can remove a child. For example, if the child requires urgent medical care or has experienced serious harm.

- By Court Order. If there is a court order requiring that the child must be removed from the home then the child may be removed.

A CPS worker has a lot of discretion when it comes to deciding if a child is in immediate danger, but they do use certain criteria to guide their decision.

If a child is removed from their home, CPS must place them in an alternative temporary placement. CPS must first try to place the child with a relative or non-related extended family member, such as a relative’s family member, before placing them in a general foster placement with strangers.

If the CPS worker decides that an immediate emergency removal of the child is necessary and removes the child, the CPS worker must file a document known as a “petition” with the Juvenile Dependency Court within two court days. The court must hold a hearing by the end of the day after the petition is filed. In the meantime, a parent or guardian can request that the CPS worker arrange visits with their child while waiting for their court hearing.

After a child is removed and put in a foster placement for 15 months, plans to terminate parental rights may begin.

Is my conversation with a CPS worker confidential?

No. Anything you say to the CPS worker can be used against you, including your mannerisms and body language. For example, a CPS worker could testify that you appeared “hostile” or “violent” because your arms were crossed or you were yelling.

You have the right to refuse to answer questions. For example, you can respond, “Now is not a good time for me, but we can talk later” or “I would like to speak with an attorney before I speak with you.” Additionally, once you know what the allegations are, you can limit your responses to relevant information and say, “I don’t think that question is relevant to the concerns you’ve raised.”

Do I have the right to a lawyer during a CPS investigation?

You have the right to contact an attorney for help at any stage of the CPS investigation process but you are not guaranteed an attorney by the state until a petition is filed against you in Juvenile Dependency Court.

To protect your rights and your family, you should contact an attorney with experience in family law and/or dependency court as soon as possible once a CPS investigation begins. Some counties do provide free legal services at the investigation stage. For example, parents in Los Angeles can contact Los Angeles Dependency Lawyers’ (LADL) parent hopeline, even before a case has been filed. In Santa Clara County, parents can contact Dependency Advocacy Center’s First Call Program. Parents statewide can contact the East Bay Family Defenders Project at Legal Services for Prisoners with Children.

Once a dependency court case is filed, each county should provide free or low-cost legal services for parents facing a case in dependency court. You can find contact information for your local county office here and ask who represents parents in your county. For example, in Los Angeles, parents are usually represented by Los Angeles Dependency Lawyers Inc.

Can a CPS worker talk to my children without my permission?

It depends. At your own home, CPS workers cannot interview your child without your consent, but they may be able to do so at your child’s school. CPS workers are not restricted in what questions they can ask, but your child is not required to answer their questions. If a CPS worker speaks with your child at their school, they must notify you afterwards that they did so.

It is best to speak with a lawyer before allowing your children to speak to a CPS worker because any responses may be used against you at a later point either in the CPS investigation or dependency court case.

Do I have to take a drug test if CPS asks me to?

No. CPS cannot force you to take a drug test without a court order that says you must take one. But your refusal can be used against you.

Do I have to sign releases for a medical examination of my child?

No. The CPS worker can ask for a medical examination of your child to help decide if there are signs of abuse or neglect, but they would need court approval to require a medical examination.

If you are comfortable with it, you can offer to have a doctor conduct an examination without signing a release. You could say, “My children already have a doctor who they are comfortable with; I will provide an examination from this doctor.”

Does CPS have to provide me with translation services if I do not speak English?

Yes. You have the right to understand what your CPS worker is saying. If you do not feel comfortable speaking English, CPS must promptly provide you with effective interpretive services. Alternatively, you may use your own interpreter if you wish, but you are not required to provide one. If you cannot read English but can read another language, CPS must provide you with translated forms in the language you understand.

What kind of support can I request if I have a disability and need help?

CPS is required to provide reasonable accommodations for clients with disabilities. Clients may include a child, birth parent, caregiver, or other person who is important in the child’s case. Once the CPS worker knows that a client has a disability, the worker must document the disability in the case record. Requests for auxiliary aids and/or services must also be documented.

If you are deaf or hard of hearing, or speech, visually, or physically impaired, you are entitled to auxiliary aids and services. Auxiliary aids may include a telecommunication device for the deaf (TDD), Braille material, taped text, qualified interpreters, or large print materials. You can request your preferred auxiliary aids and services, but access to what you prefer is not guaranteed if other effective means of assistance exist.

Am I entitled to assistance if I am unable to read or struggle with reading?

You have the right to understand what is happening during investigations and proceedings.

If you cannot read in any language, you must be provided forms in your native language, which will be read to you. CPS must provide a reader, or, if you prefer, you can bring your own reader.

Dependency Court Proceedings

What happens after a dependency petition is filed?

A petition is a type of document that gets filed with the Juvenile Dependency Court to start a dependency court case. A petition contains a list of facts that CPS thinks are enough to be considered neglect or abuse under the law. The list of facts is arranged under the categories of neglect or abuse.

The Juvenile Dependency Court is part of the Juvenile Court system and oversees cases involving allegations of child abuse or neglect filed against the parent or guardian.

Once a case begins, the court will usually hold several hearings to decide whether the allegations are true and whether the child should be made a “dependent of the court,” which means the court will have authority to make decisions about the child’s care and home placement going forward.

When do I get assigned a lawyer in my dependency case?

After a dependency petition is filed, the first hearing will be held (usually called an “initial hearing” or “detention hearing”). At that hearing, an attorney will be assigned to a parent or guardian if they do not already have one and cannot afford to hire one. Parents and guardians have the right to consult with a lawyer at any time during this court process and should do so. Children in dependency court are assigned their own separate lawyer.

During these dependency court proceedings, parents continue to have parental rights over their child, but may not have physical custody of their child and must comply with any court-mandated requirements. Parental rights include the right to decision-making over your child’s education and medical treatment, and the right to maintain regular telephone contact with your child. You also have the right to attend agency meetings that discuss your child’s needs and services like a child family team meeting.

What if I am told that the only way to avoid a dependency case is to file a petition for guardianship in probate court so my child can instead live with a relative or family friend?

In certain situations, CPS may tell parents and, more often, their relatives that they can avoid a dependency case in juvenile dependency court by instead filing a guardianship petition in probate court. This is sometimes called the “shadow” foster care system or “hidden” foster care.

By filing a guardianship petition in probate court, families can appoint another adult, usually a relative or family friend, who is not the child’s parent, to be the child’s legal guardian. This usually happens when a child’s parents are absent or unable to care for them for various reasons.

It really depends on your situation whether a guardianship is the best option for you, but your family should never be forced to file for a guardianship petition in probate court to avoid CPS opening a dependency case in the juvenile dependency court if you don’t want to.

It is important to understand that your rights as a parent are different in dependency court than in probate court. Parents in probate court do not have the right to an attorney and the probate court may not order services. Children under probate court guardianships are also not eligible for the same resources and funds that children in dependency court are.

The goal of probate court is to provide a way to appoint a new guardian, not to reunify families, and so it has fewer protections for parents and children who are separated. In addition, probate guardians may file to adopt a child in their care after two years without being required to show the parent is “unfit.”

What is best for your family depends on your current situation and whether you trust the proposed legal guardian. You should do your best to consult with an attorney if you can.

Voluntary Services

What is a “safety plan”?

Safety plans are short-term agreements to address immediate safety concerns that cannot wait until a more comprehensive plan is developed. Safety plans may be formal or informal. Safety plans may be voluntary or involuntary; involuntary safety plans are ordered by the court as explained further below.

Typically, parents have some say in their child’s placement in voluntary safety plans. A safety plan must include an end date. It should also include people beyond just the parents and CPS, and include people the parent has identified as part of their support network. You have the right to provide input on how to create safety. The plan should also lay out clear behavioral actions the parent(s) can take to demonstrate safety.

If I am offered a “safety plan,” do I have to sign it?

It depends. There are different kinds of safety plans and not all safety plans are voluntary.

If it is a formal court-ordered safety plan, then it is not voluntary. For example, a court may order that a child can be returned to the home but that their return is dependent on following a specific plan such as requiring one parent to stay out of the home.

Other informal types of safety plans are considered voluntary. However, although you can choose whether or not to sign it, if CPS believes the child’s safety is at risk and you refuse to sign it, that can result in your child’s removal.

If I am offered a “voluntary family maintenance” or “voluntary placement” agreement, do I have to sign it?

No. If CPS believes a report may be “substantiated” but is not required to file a petition with the Juvenile Dependency Court, it may instead offer a “voluntary placement agreement” or a “voluntary family maintenance agreement.” These are often called “voluntaries” or “voluntary.”

“Voluntaries” are voluntary written agreements between CPS and the parents of the child that are supposed to specify resources and a plan for managing the alleged threats to a child’s safety. These agreements must have an end date and are limited to 180 days. They usually also require parents to receive support services. Sometimes they may include a child being temporarily placed out of the parent’s custody. A child should NEVER be separated from a parent without the parent agreeing to a “voluntary” (or a court ordering the separation).

Before offering a voluntary, CPS may also ask you to agree to a safety plan, as explained above.

Voluntaries are not court-ordered but can still be harmful if families do not understand what they are agreeing to. Families should be very careful about entering into such agreements, especially without consulting with an attorney before agreeing to enter a voluntary plan.

If a CPS worker offers you a voluntary agreement, you have the right to read the plan in your primary language. Additionally, you have the right to not sign the plan. While CPS workers should not threaten to remove your children to coerce you into signing voluntary agreement, not signing can and has been used against parents if a case ultimately goes to dependency court.

Legal disclaimer. The information provided in these materials is for general educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. While the ACLU of Southern California strives to keep information accurate and up-to-date, we make no guarantees about the completeness of the information in these materials and strongly recommend that you consult with an attorney regarding your specific legal situation.