The following was first published in the Voice of OC

Mike Newman tried hard to manage his clinical depression while living at Laguna Beach’s homeless shelter, but the conditions there made it nearly impossible.

Tucked deep in secluded Laguna Canyon, the shelter is far removed from the pristine beaches and rocky coves of this picturesque and affluent community. In sharp contrast to the laid-back beauty of the city’s downtown beach area, the shelter is noisy and overcrowded—a chaotic environment that only worsened Mike’s depression and other ailments. He slept on a thin mat that aggravated his hernia. He tried to cope while being confined in close quarters with 45 other people, most of whom had mental or physical disabilities. People often had mental health crises, and some screamed all night. Paramedics came and went on a regular basis.

A long-time Laguna Beach resident, Mike, who is 53 years old, moved to the shelter about seven years ago after falling on difficult times. As the years wore on, the shelter environment became unbearable.

Mike has a major depressive disorder, a medical condition that can be brutally incapacitating. Effective management of depression can be a matter of life and death—according to the American Medical Association, up to 15 percent of cases end in suicide. For Mike, the feelings of sadness that overtake him can be as painful and intense as the loss of a loved one. “Sometimes I just want to curl up in a bed and cry,” he said. “But when I was living at the shelter, I couldn’t get away from people. It made my depression worse.”

On nights when individuals with disabilities can get shelter in Laguna, they often find themselves unable to cope with the conditions there. People with disabilities often sleep outside, even though it means running afoul of the city’s ordinances banning sleeping in public, and inviting the attention of police officers who routinely sweep through the area and ticket or threaten to ticket people huddled in the shelter’s parking lot.

These days, Mike sleeps outside every night: A couple of months ago, he was banned from the shelter for being argumentative, a common symptom when his mental disability becomes difficult to manage. Lacking any process to challenge the ban, he set up camp on the beach.

Now, Laguna Beach officers routinely roust him in the middle of the night and issue him expensive citations for sleeping in public. He has accumulated six tickets in as many weeks, which he cannot pay—tickets representing fines and fees that could easily total hundreds or even thousands of dollars. He says harassment by police officers has contributed to his depression.

The harsh treatment mandated by Laguna Beach against Mike violates the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Rehabilitation Act, which require state-funded programs to accommodate the needs of persons with disabilities. The ACLU of Southern California (ACLU SoCal) and a pro bono team at the law firm Paul Hastings, LLP have cited his case and others in a lawsuit challenging Laguna Beach’s homelessness program. Mike and the other plaintiffs are seeking accommodations such as private areas in shelters, staff training, raised beds for people who need them, a van lift, and due process protections against arbitrary denial of shelter.

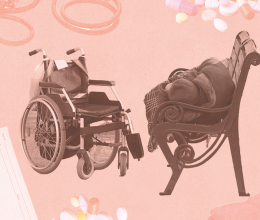

Take, for example, the situation faced by Norma Cristo, who uses a wheelchair. Because the city’s transportation van lacks a wheelchair lift, she has to pull herself inside with her one arm and one leg – or be lifted by others – when she needs a ride to the shelter. Then there’s the case of Douglas Ricks, 57, who has a degenerative spine condition and Stage 3 melanoma that has left one arm mostly useless. He finds it nearly impossible to pick himself up from the shelter’s floor mats. Even though he brought a doctor’s order for a raised sleeping surface, such as a cot, the staff repeatedly rebuffed him when he asked for an appropriate accommodation.

The lawsuit charges that not only does Laguna Beach fail to accommodate disabilities among people facing homelessness, it exacerbates those conditions by forcing them to choose between a chaotic shelter or sleeping outside and risking police harassment, fines, fees, and time in jail. Others don’t have even that choice. They are turned away from the shelter for lack of space, and staff are quick to throw them out into the dark canyon if they are disruptive or argumentative, even if those behaviors are rooted in their disabilities. Some have died along the canyon road when denied a place at the shelter.

In response, the lawsuit charges the city’s homeless program with violating Eighth Amendment protections against cruel and unusual punishment. It argues that Laguna Beach cannot issue citations for sleeping in public when violators literally have nowhere else to go.

What is most troubling is that mechanisms are already in place that could have prevented a lawsuit. The research consensus is overwhelming that providing permanent supportive housing – that is, permanent affordable apartments with wraparound services like counseling and health care – is the most effective means to address homelessness. The federal government has declared permanent supportive housing the most powerful and cost-efficient health and mental health intervention for people with disabilities who are homeless.

The City and County of Los Angeles have moved affirmatively to adopt these and related methods. In November, voters overwhelmingly approved Measure HHH, which authorizes $1.2 billion in bonds to pay for the construction of 10,000 units of housing for homeless people that will include essential support services. Also, the Los Angeles County Sheriff announced earlier this year that its deputies would be directed not to arrest homeless people for minor offenses that stem from their homelessness.

Orange County has itself crafted a 10-year plan to eliminate homelessness based on this approach – but hasn’t funded it.

A recent ACLU SoCal report detailed cost-effective solutions to implementing the plan. In 2014-15, Laguna Beach considered a permanent supportive housing project proposed by Friendship Shelter, but the project died, despite the fact that the costs could have been covered by outside funding sources. By turning away from the county’s misguided and ineffective program, Laguna Beach could have become a leader in homelessness policy. Instead, the city has chosen the much more expensive alternative of providing only short-term shelter and, like too many other municipalities across the country, citing and arresting homeless people for violating laws against public sleeping and camping.

But there are few places for them to go in in Orange County. As shown in our 2016 ACLU SoCal report, the county has devoted few of its own resources to permanent supportive housing, and county waitlists for what little exists stretch on for years.

A settlement proposal has now been offered in an open letter to the city from the lawsuits’s plaintiffs. The letter provides the city an opportunity to evaluate the needs of homeless people with disabilities – its most vulnerable residents – and comply with the law. It is high time the City changed course and adopted a more effective approach embodied in the proposed settlement.

Mike says that relief he seeks in the lawsuit is not the only reason he became a plaintiff. “I went into the lawsuit both because it’s the right thing to do and with the hope that it would help my situation, he says. “This lawsuit is bigger than me and my problems. If I can do anything to help change people’s attitude about mental illness and the stigma around it, I’ll feel like it’s been worthwhile. Laguna Beach needs to do the right thing.”

Eve Garrow is homelessness policy analyst & advocate at the ACLU of Southern California.