When I was in seventh grade, I became a spy.

This was not a schoolboy fantasy. It was the real thing, even though it was not for a foreign government or anything like that. It was right here in our home state of California, where I and other students quietly, and sometimes in secret, gathered evidence and photos of horrible conditions in public schools.

In my own school — Luther Burbank Middle School in San Francisco — the only bathroom available for students was filthy and often lacked toilet paper and soap. There were infestations of rats that were so neglected that a dead rodent remained, decomposing, in a corner of the gym for most of the 1999-2000 school year.

Textbooks were so scarce that the books had to be shared if available at all, and could not be taken home for homework. Nearly a third of the teachers lacked full credentials, and classrooms were so overcrowded that some students had to stand at the back. There was no functioning heat or air conditioning, and parts of the building were coming apart, with tiles coming down from the ceiling.

As bad as this was, it was sadly far from unusual in schools up and down the state. Once an investigation into school conditions was underway, detailed reports of similar conditions came in from hundreds of schools and were not only unsafe and unsanitary, but also made it nearly impossible for us to focus and get a good education.

The vast majority of these schools with the most dire conditions had one thing in common — a majority of the students enrolled in them were not white.

The outcome of the investigative work by students, parents, guardians, attorneys, education experts and activists was Williams v. California, a historic lawsuit filed in 2000. Four years later, it resulted in a settlement that called for almost $1 billion in improvements.

I am proud that my name ended up on the lawsuit, but there were nearly 100 other students listed in the class action.

It all started when my seventh-grade homeroom teacher, Mr. Nawa, asked the class, “How do you like your school?” The response came quick — we immediately raised our hands and started talking about the things we did not like, including the rats, bathrooms, not enough textbooks, tiles falling from the ceiling of our gym.

(Jason Nawa was in his first year of teaching social studies at Eli’s school when he posed the question to students. In a later deposition he confirmed the students’ assessments, including that the bathroom conditions were “disgusting” and that he had only enough textbooks for one class of social studies even though he taught four classes).

Mr. Nawa introduced the class and our parents to then-ACLU SoCal attorney Catherine Lhamon and Public Advocates attorney John Affeldt. Meeting them helped us start the process of documenting conditions at my school. At first, I was a bit scared to get involved. Thankfully, I had a father who assuaged my fears. He was a native of Western Samoan Island and a proud U.S. Army veteran, and he always believed in fighting for your rights and being of service to others — values that he instilled in me.

With my dad’s backing, I provided testimony and even took photos, which was challenging to do in secret. This was years before the wide use of smartphone cameras — all I had was a Polaroid that I had to hand crank between pictures. But I ended up getting photos of a bathroom, missing ceiling tiles, and other shots used in the case.

Throughout the state, students, parents, and others were doing their own investigating, and as a result, numerous examples of dire situations in California public schools were featured in the lawsuit. Here are just a few of those examples in Southern California:

- At Berendo Middle School in Los Angeles, there were no textbooks for some of the English and history classes. And the teacher shortage was so critical that students were regularly shown non-educational movies — like “Blair Witch Project,” “Scream,” and “The Sixth Sense” — to pass class time.

- At Crenshaw Senior High School in L.A., students regularly saw rats, mice, and roaches. Several classes were so overcrowded that students had to stand or sit on counters, using boards to write on because they didn’t have desks.

- At Susan Miller Dorsey Senior High School in L.A., students in some math classes didn’t have books, leaving them to copy problems from the board with no written instructions or examples. Teachers set rat traps that were cleared out by janitors as frequently as every other day. There was no heat, and some windows couldn’t be shut, leaving students to wear coats, hats, and gloves during winter.

- At Frances Willard Elementary School in Rosemead, only 13% (or nearly one out of every 10 teachers) were fully accredited.

- At John C. Fremont Senior High School in L.A., as many as three students had to share a single book in some classes. Although there were 4,200 people at the school, there were only four functioning bathroom stalls for girls.

- Huntington Park Senior High School in Huntington Park was so overcrowded that students couldn’t enroll in some core subjects, such as math. Some students would go an entire school year without taking core subjects.

A settlement agreement to the lawsuit was reached in 2004. It called for $800 million to be spent on repairs to conditions that threatened health and safety at schools. Among other provisions was that $139 million would be spent to equip students with textbooks, and ongoing every student is meant to be provided with a textbook to use in class and take home for homework. New standards were set for teacher qualifications and for county superintendent, inspections of schools.

And every school district had to provide a process for students and others to file complaints over unsafe or unhealthy school conditions, insufficient instructional materials, and teacher vacancies. Thousands of students across the state have used the complaint process in the years since the settlement was approved.

The announcement of the settlement allowed me to speak next to then-governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. I wasn’t used to standing in front of bright lights and cameras, but it was an awesome moment for me and my family.

I look back now and can’t help but think how brave it was for me and my classmates to take matters into our own hands. Little did we know that the photos we snuck to take and our speaking up at a young age would lead to something so significant.

The settlement came as I was finishing high school, so I wasn't able to reap the benefits of what we worked for. But I am so proud of what we accomplished, and my father and I are thankful for the opportunity of a lifetime to create the change we wanted to see.

We know the work toward education equity is not over, but we hope our story serves as testimony that when you work for truth and justice, we can hold our state leaders accountable and make a difference for generations to come.

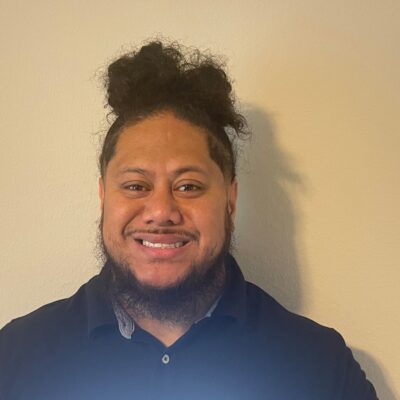

Eliezer “Eli” Williams was a student at Luther Burbank Middle School in northern California and the named plaintiff in the landmark ACLU SoCal case Williams v. California. Williams is now a high school English teacher in Texas.

This article is part of the ACLU SoCal's centennial series, exploring the affiliate's long and evolving work and impact in the southland. The series lifts historic milestones and facts documented in the "Open Forum," the ACLU SoCal's newsletter published from 1924 to 2004. This year, in partnership with the California Historical Society, the ACLU SoCal has published and digitized the "Open Forum" in its entirety. Explore the archives and read more about how Eli Williams and the ACLU SoCal continue to fight for education equity.