“A counselor on a domestic violence hotline told me my life was more important than things and that I should get away quickly,” Deborah Kraft recalled. Leaving everything behind, Deborah drove west until she reached Orange County, where she entered the homeless shelter system.

Deborah knew the path forward would be challenging. But she never imagined that the shelters she relied on for help would be as abusive as the relationship she left behind.

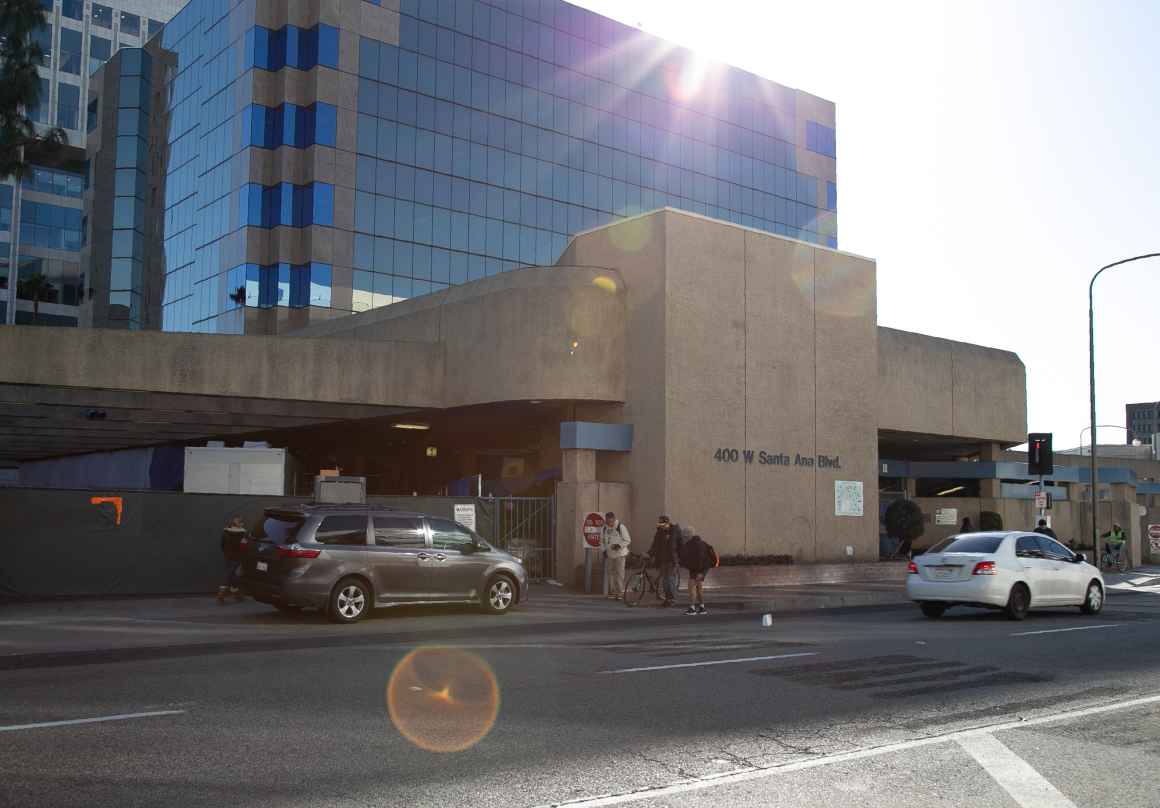

At the "Courtyard," a gloomy, open-air shelter located in an old bus terminal, Deborah faced constant sexual harassment and dangerously filthy conditions. One staff member woke her up every morning by rubbing his fingers in her palm and asking her if she still had a boyfriend. Others made crude sexual comments and leered at her. She put up with portable toilets smeared with human waste and filled to the brim with raw sewage—the shelter stank of urine. With no temperature control, the place was overheated during the summer and frigid in the winter.

During storms, the rain would blow into the shelter. Bedbugs dug into her skin. She was hospitalized several times with pneumonia, which she attributed to the overcrowded and unsanitary conditions. She had nowhere else to live, so she tried not to complain. She noticed that staff retaliated against people who dared to speak out about the abusive conditions—sometimes by evicting them.

Deborah could not help wondering whether she would have been better off staying with the person who had terrorized her.

The abusive conditions Deborah endured are not only harmful, they are also unlawful. And as documented in the ACLU of Southern California 2019 report, “This Place is Slowly Killing Me:” Abuse and Neglect in Orange County Emergency Shelters", they are all too common in Orange County shelters.

The ACLU SoCal and a pro bono team at the law firm Kirkland and Ellis have cited the case of Deborah Kraft and others in a lawsuit charging that Orange County, the City of Anaheim, and the contractors who provide shelter and security services have violated the civil rights of the people they are supposed to care for. The charges include violations of state anti-discrimination and sexual harassment laws, California Health and Safety Codes, the right of freedom of movement, equal protection laws, and the right to free speech and expression.

Some of the policies and practices the lawsuit challenges actually prevent shelter residents from escaping homelessness. La Mesa and Bridges at Kraemer Place shelters enforce so-called “Good Neighbor” policies that place extreme restrictions on residents’ ability to get into or out of the shelter. In reality, these policies function as “lock in/shut out” policies that profoundly limit residents’ freedom of movement, making it much more difficult for them to hold down jobs or obtain benefits.

These policies prevent residents from walking or biking to and from the shelter as a way to keep them segregated from, and invisible to, others living near the shelters. The only way most people can leave is to sign up for a shuttle to the designated drop off locations—and there are only enough spots for a fraction of the residents.

Wendy Powitzky, who lived at the La Mesa shelter, wanted to work and earn enough money to rent her own apartment. But the shuttle dropped her off far from her place of employment, which required her to take several buses. A trip that should have taken 20 minutes took several hours. She was unable to make it back to the shelter before curfew and had to give up her job. “It feels like a FEMA camp,” she said of the shelter. “Little by little, they are making this more like a detention facility.”

Other practices, like the retaliation shelter residents face for speaking out publicly about abuses, are meant to cover up malfeasance, enabling it to continue.

The lawsuit sends a clear message that nobody should have to give up their civil rights in exchange for a roof over their head. In fact, as community members with some of the most pressing needs in society, it is imperative that shelter residents receive services that are responsive, caring, high quality, and that treat them with the dignity and respect to which they are entitled.

Of course, shelters do nothing to address the real causes of Orange County’s homelessness crisis—namely, a dire shortage of subsidized affordable housing and skyrocketing rent in the private market. In fact, the failure of local governments to invest in affordable housing, along with their emphasis on shelters as a response to homelessness, has allowed the problem to grow.

But until our elected officials muster the political will to end homelessness by guaranteeing affordable housing to everyone who needs it, we must ensure that shelters are safe and habitable, follow the law, and are held accountable when they don’t.