Ange Samma, a 22-year-old green card holder from Burkina Faso, came to the United States seven years ago, when he was still a teenager. After studying electrical engineering at community college, he decided to enlist in the U.S. Army in 2018. He wanted to give back to his adopted country and also hoped joining the military would help him achieve his goal of becoming an electrical engineer.

Ange currently serves on active duty as a soldier in South Korea. But despite serving this country on a U.S. military base in a foreign country, he still hasn’t been able to obtain citizenship through his military service, as required by law. Without citizenship, Ange faces risks his U.S. soldier counterparts do not, for he does not have a right to consular services and protection. Ange also fears that his lack of citizenship sets him apart from his fellow soldiers serving in South Korea.

Ange is unable to exercise the various privileges afforded to U.S. citizens, including voting in an election year, and sponsoring immediate family members. Ange has also found that, without citizenship, many of the roles in the military best suited to his skills and career goals are closed off to him.

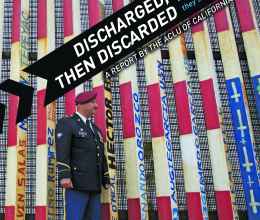

Today we, together with the ACLU and the ACLU of the District of Columbia, filed a class action lawsuit on behalf of Ange and thousands of non-citizens serving in the nation’s military who, like him, are entitled to apply for naturalization but have been obstructed from doing so. The lawsuit — Samma v. Department of Defense — challenges the Trump administration’s 2017 policy making it difficult, if not impossible, for non-citizen U.S. military members to obtain expedited citizenship, as Congress has long promised them.

Non-citizens have enlisted in the U.S. military in large numbers throughout our nation’s history, serving in the Revolutionary War and in every major conflict since the founding of the republic. They continue to make up a significant number of those fighting in today’s wars. Between 2011 and 2015, there was an average of about 10,000 non-citizens serving in the Army per year. The Department of Defense estimates that approximately 5,000 green card holders enlist in the military every year.

For more than 200 years, Congress has recognized the critical role non-citizens play in the military by promising them an expedited path to citizenship. Since 1952, that promise has been reflected in a provision of the Immigration and Nationality Act, which provides that any non-citizen who has served honorably in the U.S. military during a period of armed conflict may naturalize, regardless of their immigration status or length of residence in the United States. By waiving the typical requirements for naturalization, Congress intended for non-citizens to apply to naturalize almost immediately upon entering service and prior to deployment. Since 9/11, over 100,000 non-citizens have taken this expedited path to citizenship to naturalize on the basis of their military service.

The government’s 2017 policy deprives non-citizen service members of the path to citizenship promised by Congress and that they have earned through honorable military service. For decades, non-citizens could obtain the certifications of honorable service required for naturalization almost immediately upon entering service; now they must wait months, long after they have deployed to their duty stations. The policy also forces non-citizens to submit to lengthier, more invasive background checks and severely restricts the number of officials who can issue such certifications.

Government statistics demonstrate the devastating impact the government’s 2017 policy change has had on military naturalizations. In the year following its implementation, the government reported a 72-percent drop in military naturalization applications from pre-policy levels.

The 2017 policy is part of the Trump administration’s broader assault on immigrants, including those serving in the military. The government has specifically targeted immigrant service members through policies designed to deter them from enlisting. Several of our clients were also subjected to this policy and had to endure months, in some cases years, of waiting before they could ship to basic training and begin their service. Once enlisted, they and thousands of other immigrant service members must wait again, under the policy they’re now challenging, to become citizens. ICE has also ramped up its deportation of veterans, disregarding policies that require the agency to consider military service in immigration cases.

The government’s policy is causing real harm to immigrant service members. Two of our clients, whose immigration statuses are in question, fear the government may deport them at any time. Many of our clients are also unable to access professional advancement opportunities within the military because so many roles, including more specialized positions that suit their skill sets, are only available to U.S. citizens. Others are unable to sponsor their families to unite with them in the U.S.

The government’s policy also harms the military because immigrants are so critical to it. Non-citizen enlistment is integral to maintaining military recruitment numbers; in nearly every recruitment year between 2002 and 2013, the Army would have failed its recruitment goals for its active duty force without non-citizen enlistments. The Department of Defense itself has recognized that non-citizen recruits tend to be of “higher quality” than their citizen counterparts. They also perform better than U.S. citizen recruits once they enter the military, exhibiting substantially lower attrition rates. Finally, non-citizens are likely to possess skills vital to the military, including linguistic diversity and medical and information-technology expertise.

The promise of citizenship Congress made to non-citizen service members is not just an important recruitment tool. It is a moral imperative embedded in our history, values, and laws. If you are willing to make the ultimate sacrifice for America, you are — and should be — entitled to be an American.