Some California high school students were being sent home from school early or warehoused in the auditorium rather than being assigned meaningful academic classes. As hard as it may be to believe, last year countless students at Los Angeles’ Jefferson High School, for example, didn’t have a complete schedule more than six weeks into the school year.

Others had not been assigned classes they needed for graduation and were instead assigned to bogus classes with no educational content. Still others were simply sent home early.

Assemblymember Reginald Byron Jones-Sawyer, Sr., whose district sits in South Los Angeles, decided to do something to end these practices. He introduced AB 1012 to protect the fundamental right to equal educational opportunity. The bill was signed into law in October.

The new law creates a state-level backstop to protect students when there is such a fundamental breakdown at the school level. The ACLU of California was proud to support this important legislation and worked closely with Assemblymember Jones-Sawyer on the bill language.

We are pleased that state leaders recognized that schools serving almost exclusively low-income students of color should not be able to send kids home early or warehouse them in fake classes that have no educational content or value.

AB 1012 represents another step toward making the constitutional right to equal educational opportunity more real. We at the ACLU want to raise awareness about this important law and address questions about its scope.

This blog is an initial attempt to explain what the bill does and provide context for the intent that led to its enactment. The ACLU is also working with other stakeholders to provide more formal legal guidance later this spring.

AB 1012 limits the ability of schools to assign high school students to “a course without educational content” and to courses the student has taken and passed. Both situations have specific meanings defined within AB 1012:

- Course without educational content includes three distinct components and applies much more narrowly than what it might in casual conversation:

- Sending a student home before the end of the school day, called “early release” or “home period” in some schools.

- Assigning multiple students to be student aides/teacher assistants to one teacher during the same class period while that teacher was teaching a class.

- Not assigning a student to a class during the school day, called “free period” in some schools.

- Course the student has taken and passed excludes classes that are designed to be taken multiple times because the course content varies from semester to semester. This definition is designed to exclude physical education, band, chorus, and art classes that students may take several times because they do not cover identical content each semester.

Notably, AB 1012 does not create an absolute ban on such courses. Rather, it provides that students can be assigned to such courses if they (or their parent/guardian) consent to the course assignment in writing and a school administrator makes an individualized determination, confirmed in writing, that the assignment will benefit the student.

Finally, AB 1012 creates a complaint process so that any student, parent/guardian, teacher or member of the public can correct a situation where a student is given a course that does not meet requirements of AB 1012.

This provision was intended to create a simple, accessible way for any issues to be raised and resolved quickly. It is not about playing “gotcha,” but about ensuring district and school staff can resolve any problems that may arise.

There has been some confusion about the “service course” component of the definition for “courses without educational content.” In developing this definition the intent was to ensure that multiple students were not assigned to assist the same teacher during a period when that teacher was teaching a curricular course. It prevents multiple students from being assigned as teacher aides for the same course period.

The language is not as clear as it could have been on this point. We are working on a fix through the budget process to ensure the language is as clear as possible before the bill goes into effect for the 2016-17 school year.

But, given our role in crafting the bill language, we wanted to provide this information about the underlying intent as we work to ensure the statutory language is as clear as possible.

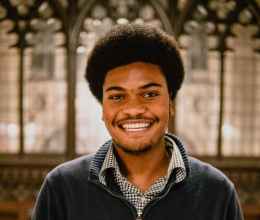

Victor Leung is staff attorney at the ACLU of Southern California.